Whitehot Magazine

February 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

February 2026

February 2010, Moments in Pop Culture and the Everyday: an Interview with Michael Halsband

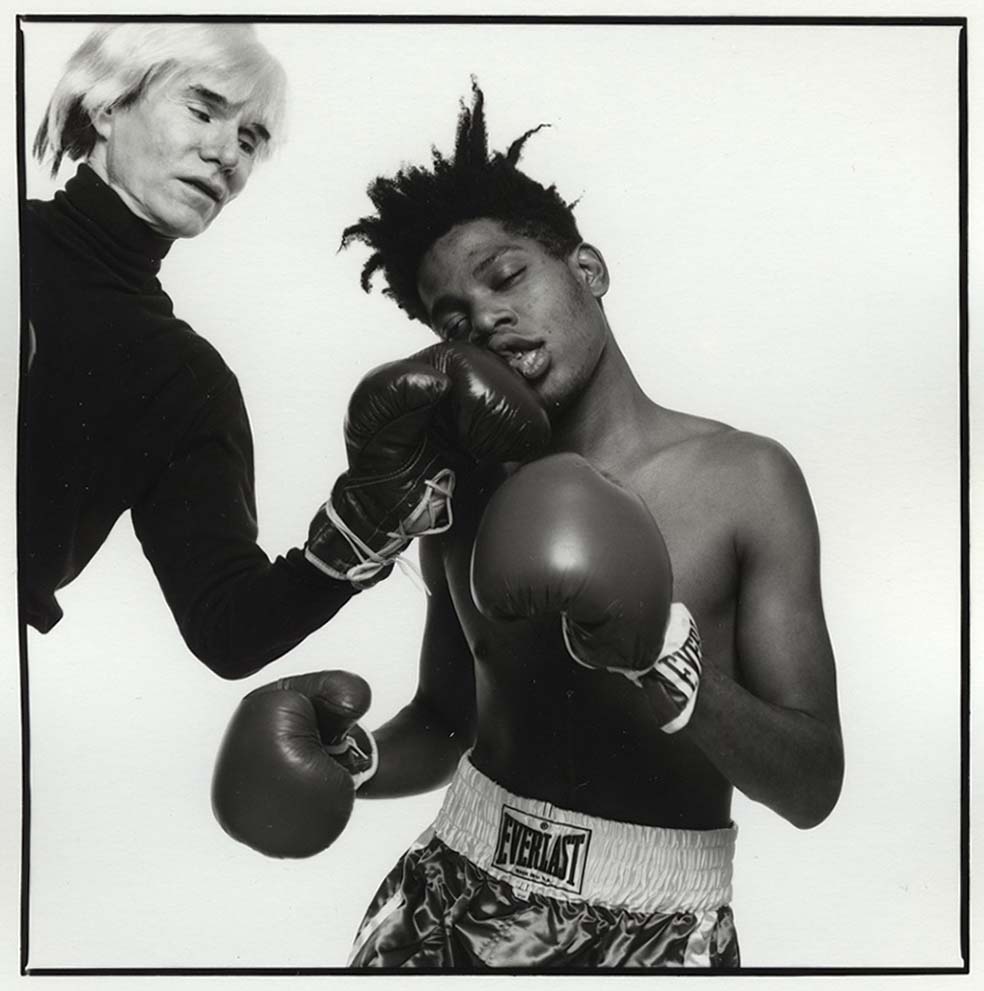

Knock Out Punch, Andy Warhol & Jean-Michel Basquiat Studio, New York July 10, 1985

Silver Print Silver Gelatin Print Signed, titled, dated, and numbered on verso

Photograph by Michael Halsband

Moments in Pop Culture and the Everyday: an Interview with Michael Halsband

Michael Halsband is a portrait photographer who has had his hand on the pulse of American popular culture since 1980. Having worked with Klaus Nomi, Joey Arias, Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat and the Rolling Stones, Halsband utilizes the photograph as an interface that exposes the dense layers of personality, creativity and talent that underwrite both the alternative and mainstream. When I met with the photographer at his New York studio in December, Halsband discussed the complicated nature of celebrity, ballet, nude photography and surfers – subjects that have had a profound effect on his work. And yet he did not hesitate to honor the contributions of Irving Penn and Richard Avedon to the profession of photography.

Jill Connor: What is your approach to portrait photography? Is it strictly contextualized or casual?

Michael Halsband: I want to be a fly on the wall and observe, like a ghost. It enables me to really feel and see as much of the truth in a situation where I’m not imposing myself or threatening with my presence. But it sort of surprises me that I am visible, when people say, “Oh you’re known!” Someone said to me the other day, “You really undersell yourself.” But I have to, it’s my job since I don’t want anyone to be intimidated by me. Maybe it’s flawed to a certain degree because of that. Presence gets in your way if you’re too well-known. On the one hand there is this sort of latent desire to want to be recognized and celebrated, but then there’s this fear and concern that it might prevent me from what I would actually like to be able to do. How can I be successful enough without distorting my approach? To serve the work, I have to disappear.

Photography became such a popular profession after the movie Blow Up from 1966, making the fashion photographer equal to being like that of a rock star. My heroes – sociologists, archaeologists, people who studied our cultures – all inspired me to flatten the whole thing and take the glamour out of it. It’s about our civilization and our culture. It’s about more than just famous people, since every shoot has to be on level ground, with no one having the upper hand. When I’m photographing it is letting what is, be. The expression has to be without props, to actually let go of all influences and your own projections. It’s all about just relaxing and being yourself. I try to convey my sitters to that place.

JC: Klaus Nomi had a short but profound influence upon the East Village art scene during the early 1980s. How did your paths cross, leading to the development of his famous, space-like look?

MH: Klaus Nomi’s portrait was made in February of 1980, and was part of my senior thesis at the School of Visual Arts (SVA). I knew Joey Arias, who worked at Fiorucci‘s, through a girlfriend of mine at the time. Then I saw he and Klaus Nomi live on stage with David Bowie when he performed for Saturday Night Live. I thought it would be cool to photograph them because they were so weird and so accessible. Someone like Bowie seemed way out of the realm of possibility, especially when compared to those performers who were part of the local scene. I approached Joey and he said, “Yea, I could get Klaus for you,” but I decided to photograph both of them.

Klaus showed up with that space-like outfit that had just been made by a costume designer. He said that it would be great for me to be the first person to photograph him in that outfit, so we worked on it. He and Joey loved working with me since I was into precision, trying to find a balanced portrait. In that same series it was all of Klaus Nomi’s group, then Billy Boy and then other characters that spun off from that scene. So I just tried to document them all.

Somewhere along the line they thought that I just decided to settle in with this one group, with these characters and just get more – try to approach it over and over and over again. The body count wasn’t as important to me as with other photographers.

I was only interested in photographing the same characters repeatedly so as to reveal more depth in them, as well as myself. I re-worked the same images, with the same subject matter on either white paper or white paper unlit, keeping everything very simple. The sitters were the designers of their own photographs by the actions and shapes they created in front of the camera.

Klaus Nomi, Studio, New York February, 1980

Silver Gelatin Print Signed, titled, dated, and numbered on verso

Photograph by Michael Halsband

JC: Nomi’s music career took off soon afterward in France. What came your way after SVA?

MH: Then I got this offer from the Rolling Stones’ record label to go and work on a cover portrait of Keith Richards for a Rolling Stone magazine cover. I went up to start working on it, where they were rehearsing on a farm in Massachusetts. It was just Keith and I shooting and working. We kept re-shooting it, trying different things. It never really felt right. Suddenly the idea was to try it on the road, and I was soon on tour with them. Finally we did set up a makeshift studio in the middle of the night in a Los Angeles hotel room. It turned out Rolling Stone magazine published a different image that they had on file since they had been waiting too long. Then Mick Jagger asked me if I wanted to continue to work as their tour photographer since he thought I had the most comprehensive documentation of the tour so far. I thought, “Well, I have nothing else waiting for me back in New York. Yes! Let’s do it!” It was like a dream come true. I was aware of the work that other photographers had done, so I already knew what worked and what didn’t work for me.

It was challenging, especially in 1981, when technology was at a place where motor drives were one of the most exciting features. The fact that you could shoot 3 frames in a second was great. It was really hard to shoot into the stage light. I wasn’t approaching it so much as a normal rock photographer would have since I had the freedom to move around. There was no pressing commercial use that limited me in any way at that time. The beauty of my position was that I was an outsider even though I was part of the group. I was included but I was invisible.

Mick Jagger & Keith Richards, 1981, Tattoo You North American Tour

Color C-Print Silver Gelatin Print Signed, titled, dated, and numbered on verso

Photograph by Michael Halsband

JC: What was life like after the Rolling Stones? That must have been quite an adjustment.

MH: It was sort of the beginning of a lot of ideas for me, because I had thought a lot about that whole journalistic approach and the social study of it. I’m sort of dedicated to Western Pop Culture, but from the perspective of someone who was born into it without completely buying into it. I like being in the middle of it but I don’t feel like I have to be a part of it in any way. When that tour was over, I thought to myself, I did it. It was like a dream come true. My thoughts were leaning toward fashion, still-life, documentary and portraits. I started to pursue fashion in the Summer and Fall of 1982. Things fell together pretty quickly, and all of a sudden I was off and running with an agent going to London, Paris and back to New York. I started getting little jobs with GQ, Self and was then working with Condé Nast regularly. 1983 to 1985 was just fashion.

My first project for GQ was a group portrait of the Downtown art and fashion scene. I then had the idea of doing pictures of outdoor, upbeat, natural and healthy girls. Basically portraying women as women, who celebrated who they were in an upbeat way. Then I discovered Toni Frissell’s work from the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s, and realized I was doing the same thing but in the 1980s, with the same energy and the same courageous aspect to it. I got so turned off of fashion by the decadent 1990s. I found out that other people were not taking fashion photography as seriously as I was, in terms of it actually having some long-lasting value. It occurred to me that it really had no long-lasting value, making all this work sort of meaningless.

JC: Then in 1985 you worked with Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol, creating the picture for the boxer show poster. Did this have any connection with your previous encounter with Klaus Nomi?

MH: Jean-Michel and I met at a photo sitting, at Mr. Chow’s, that I did of a group of contemporary artists for Eric Good and the owners of Area. We didn’t really speak at all; if we did it was brief. I got a call a couple of months later from Page Powell who called me and asked if I wanted to come to a dinner in the back room of a restaurant that Andy was giving. It wasn’t unusual but I said “Ok, yea cool.” When I showed up, there was one seat left at this big table, and it happened to be next to Jean-Michel. I sat down, and he started talking to me. I thought he was being nice. He said, “I have been a fan of your work for 5 years. The first work I saw of yours was the portraits you did of Klaus Nomi.”

It was so exact and so honest that I was just taken by that, just sold, and I knew he was the real thing. He started talking to me about this show they were working on. I was half paying attention. He said, “We want do this poster, a boxing poster. Would you do the pictures for us ?” I said, “Absolutely.” Then Jean-Michel yelled across the table, “Andy! Andy! Michael’s going to do the pictures for us, for the boxing poster.” Andy said, “Oh, I thought we already asked Robert Mapplethorpe to do it.” He said, “Yea, well Michael’s going to do it.” And Andy said, “Oh, well I love Michael’s work, too. I’ve always loved working with Michael, that would be great.”

JC: What about the day they came over here, to your studio, and stood in front of the white background?

MH: The shoot took place in 1985, five years into my career. It wasn’t that I was photographing Jean-Michel or Andy; it was the fact that we had aligned and clicked in to something, in a split moment and I was there pressing the button. I shot about 15 rolls of film but not always with the two of them together: sometimes singles, doubles, in different variations of the clothing that they had. It was almost like them as they were, before we got to the Everlast shorts. It evolved, and by the end it was Andy wearing a black turtleneck with the boxing shorts over his jeans, and Jean-Michel only in the boxing trunks with boxing gloves. It was what each of them evolved into by the end of the shoot, and then we were done.

I remember a few instances, one specifically, where Jean-Michel had an idea and he posed Andy where it looked like he was giving him an upper cut, then put himself in the picture and laid his face on the glove making it look like he was getting punched. I tilted the camera and instantly it came together, compensating for the fact that Andy was like a stiff board. All of us made this moment together. It all happened without me thinking about it.

To me they weren’t what they are today. In the end, the roll of film didn’t mean that much to me. Andy was a famous artist, and I did feel like it was great to always photograph him. But I didn’t have a sense of scale of him, because he was extremely low key. It was just 3 years later that both of them would be dead. And then it became the photo, this iconic image that took on this life of its own.

JC: Did you ever intersect with Irving Penn?

MH: Only as a huge fan. I actually saw him at Marlborough gallery in the early 1980s when he did the nudes. When working on Surf Book (2005), I was in Barnes and Noble the day I was going to fly to Hong Kong. I was with this person who was helping me with the production of the book and he said to me, “Pick two books that reflect the same quality you would like to see in your book.” I pulled Annie Leibovitz’s American Music book from 2003 and Irving Penn’s Passage from 1991, the two that come close to what I was looking for. My colleague’s response was, “You just chose the two books in the history of printed photography that almost bankrupted the publishers.”

I set off to do something better than that, intending to be in Hong Kong for five to seven days on press. I ended up there for 60 days. The book came out to about three times what we expected it to cost, but it looked amazing and needless to say we will never see the money that we spent on it back. But that’s what you do. Those people like Penn and Avedon were obsessed with perfection and quality. I think perfection is defined, and yet there is imperfection that requires a special balance of all those elements. So many people are not exposed to what good printing can achieve, nor do they have the ability to judge that - especially if either a publisher or a packager is involved.

For me, it’s like no compromise. Either get it right 100-percent, the way I want it, or move on to the next scenario. I recently read a quote by Avedon, about maintaining things of the past in the most pure and perfect way possible - that was what photography was. I’m not here to imitate anybody but I’m definitely here to uphold that philosophy and that approach. This is usually met with such resistance today, because there is another form challenging photography, but it’s not photography.

JC: What drew you to photograph ballet dancers after leaving fashion?

MH: The new owner of Danskin approached me to do an ad campaign for Danskin with the American Ballet School, to continue the campaign as Avedon had left it but going deeper into the world behind the stage, capturing the rehearsals and the class-atmosphere of ballet. Ballet was charming in a way of being so special, so rarified. Oddly, it was a world I had never come across even though it completely intersected with fashion. Ballet was not something that had really interested me, but I thought it was very intimate and high-action with this absolute perfection. It had to be the perfect movement in its perfect moment, in the perfect light. Eventually Danskin wanted to compete with Nike and go more in the sports direction, but when I was asked by the American Ballet School to do something with them, Danskin was very interested in helping. We worked on it for 6 years and created 6 essays. I had started this in 1986. However toward the end of that project, I started to become interested in photographing nudes.

Melissa & Jackie, Hotel Seventeen, New York March 3, 1996

Color C-print Silver Gelatin Print Signed, titled, dated, and numbered on verso

Photograph by Michael Halsband

JC: After moving on to nude portraiture, how did you maintain that sense of no-context, without being drowned by a sense of fetish?

MH: I had bought many books on the subject, looking at the representation of nude form as well as erotica in both America and Europe. I came to the conclusion that there was a lot of lying going on in nude photography: there was this sort of repressed thing portrayed by the Europeans and Americans. It looked like either a sort of humor was applied to it, or the subject was goddess-like, appearing really ugly or static in a way that objectified women.

I decided that I was going to be really honest. I wanted to find out how women like sex. I wanted them to control the picture while I served the medium as the photographer. Some sitters would come in and just take their clothes off. I would then tell them to approach it more slowly, to be seductive in their own way. It started to evolve to where people would come with their own fantasies and their own clothes. At first I was projecting stuff, and I would bring clothes. Then they started to bring their own things once they got the hang of it. It was self-portraiture, even though the pictures were chosen moments edited out of their own fantasies.

The most interesting subject was working with a girl who had never been photographed before. It was a rather virginal experience. She was great and it was extremely beautiful. I thought that I could have done everything with this project that was possible. I’ve heard people say about Avedon’s portraits that he had contempt for people. If Avedon had contempt for people, I have complete love for them. But I don’t want to manipulate or objectify them. I have not been looking for the dramatic tension, whereas everything with Avedon was very driven by drama. He needed that in every image since that is what people responded to and what powered his work.

But what more do you have to do except just be there? To let the viewer read it with any sort of animation is a prop. Posturing is a prop. The camera itself represents something, and it’s very intimidating. It takes the person away from being in the moment. My consciousness is far different from the sitter’s. I don’t hide behind the camera, but rather I stand right next to the lens and see what’s going on. The sitter and I are facing each other in a non-confrontational way. I’m making the picture for you, that’s my job.

Mara Van Leyen, Studio, New York, June 2009

10x8 Silver Gelatin contact Print Signed, titled, dated, and numbered on verso

Photograph by Michael Halsband

Photographer Michael Halsband is represented by Salomon Contemporary.

Jill Conner

Jill Conner is an art critic and curator based in New York City. She is currently the New York Editor for Whitehot Magazine and writes for other publications such as Afterimage, ArtUS, Sculpture and Art in America.